AT THE HEIGHT of troubles over the desegregation of South Boston's housing projects not so many years ago, a young African-American and a freckled redhead, obviously Irish-American, cross paths at the edge of the Old Colony Housing Project and nearly come to blows. They take off their shirts, ready to go at each other. To add the weight of historic supremacy the Irish kid backs up and threatens to beat down the black kid, "just like my great-great-grandfather beat down his slaves."

Now, since anything is possible, maybe the descendants of a plantation slave master wound up in the Old Colony project. And I suppose there's a slight chance that the great-great-grandfather of a kid with the map of Ireland on his face actually owned slaves. But it's not likely.

Unlike other European countries, Ireland was on the receiving end of colonization during the years when the British Empire emerged - and slavery flourished in Anglo-America. So those two teenagers in Southie had a lot of history in common, and not just because both lived in a housing project.

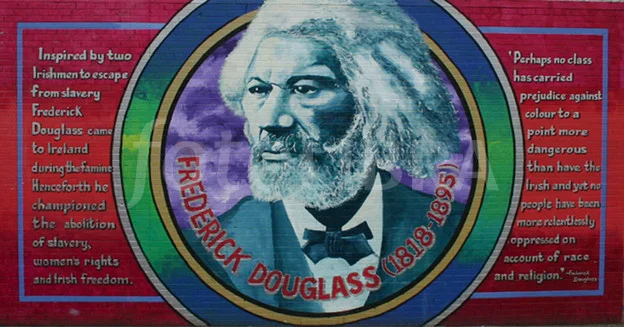

But history is too easily lost across generations and, with it, all context. To build international support for the abolition of slavery in America, Frederick Douglass visited Ireland in 1845 to speak at Irish liberator Daniel O'Connell's huge "monster meetings." He met a warm reception. "Of all places to witness human misery, ignorance, degradation, filth, and wretchedness, the Irish hut is preeminent," Douglass said in a letter to fellow abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. "I see much here to remind me of my former condition." Yet few Americans today, of any ancestry, know of such cross-cultural moments. Our cultural amnesia and loss of history made race antagonisms in Boston all the more tragic - a missed opportunity for a city that once embodied "common ground" within the working class, and across ethnicity, as no other city did.

Today, Easter Monday, is the anniversary of the Easter Rising of 1916, when Irish rebels rose up and declared independence from Britain, with the stated intention of establishing a worker's republic with "equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens ... oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien government." The declaration's concern for individual rights and pursuit of happiness applied to man and woman, Catholic and Protestant, descendant of colonist and descendant of colonizer.

Unfortunately, British historians have branded Irish commemoration of the rebels' strike as a glorification of terrorism. When Irish-Americans remember Ireland's history of colonization, it is often done in a sentimental way - "look how far we've come" - rather than as a point of reference for understanding cases of oppression today. In Boston especially, Irish-Americans' pull-ourselves-up-by-our-own-bootstraps history has been used to bolster intolerance for other ethnic groups' complaints.

Growing up in South Boston's housing projects, I wanted nothing to do with history. I reinvented myself as a post-modern punk rock youth who believed our roots balkanized us and bound us to false perceptions of who we are. I sought to erase ethnicity, to start all over. That is, until I visited Ireland - reluctantly - at age 19. There I discovered a living history, a deeper meaning to the Easter Rising than the guns or romanticism. I learned how Northern Ireland's Catholics, in their struggle in the 1970s for basic voting rights and access to housing and jobs, had looked to the African-American civil rights movement for guidance. Returning to Southie's projects, I imagined how the context of Irish history might have changed race relations among children, and even adults, before all was lost in the battle to "stand our ground" in the neighborhoods.

Much was lost, but not all. Not yet. Today, Boston's working and middle classes, from Southie to Roxbury, find their neighborhoods increasingly unaffordable. The racial turf wars of the past are largely over. Anyone with a place to live merely wants to hold on to it, no matter who is living next door.

It is now incumbent upon us to find common ground across all difference, to organize for affordable housing, safe streets, and quality schools. History teaches us that if we fail to see what we have in common, even while living together, then we will lose everything - together.

© Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.